The Chilean lithium industry has suffered from comparatively restrained growth predictions, with many suggesting the once largest producer could lag behind its global competitors. But with the new year comes a new hope: as the change in presidency signals reconciliation between SQM and CORFO, there are signs that both may be perfectly placed to take advantage of China’s rising appetite for NEVs.

It has been an eventful few months for Sociedad Química y Minera de Chile (SQM). Since September 2017, when Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan Inc. announced it was selling its 32% stake in SQM as a condition upon the China and India’s approval of their merger with Agrium Inc., there has been a significant amount of commotion among investors keen to gain a substantial foothold in the lithium market.

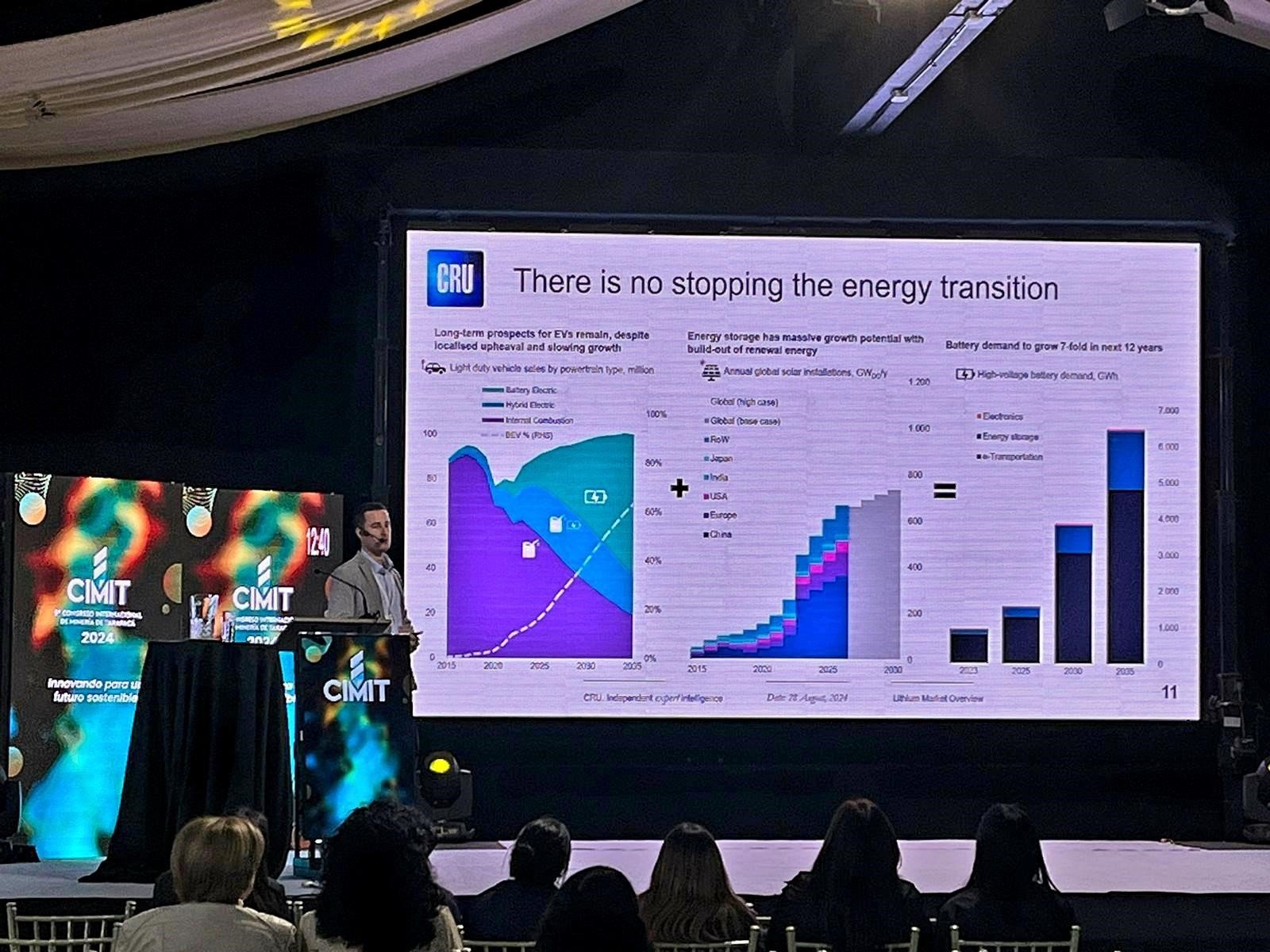

Such interest comes as little surprise; the sale offers a large stake and three board positions in a company that is a major producer in a historically highly concentrated market, controlling 21% and 9% respectively of lithium carbonate and hydroxide capacity globally. SQM is one of only two companies – Albemarle being the other – licensed to extract lithium in Chile, the country with the largest lithium reserve deposits in the world, and their Salar de Atacama brine asset offers a high lithium output at a low operating cost. With Chinese EV policy precipitating a rising appetite for lithium-ion batteries since its first NEV program was introduced in 2010 – an appetite that was compounded this year by the implementation of a credit quota system which requires carmakers to sell a minimum of 10% NEVs by 2019 to qualify – growth in lithium demand displays no signs of slowing despite the market already being in deficit, and many firms are exploiting this with new projects that sit much higher on the cost curve than Atacama.

SQM has been unable to make full use of the current positive outlook, hindered by its ongoing spat with the Chilean regulatory agency CORFO. But with a new deal struck between CORFO and SQM, circumstances have changed; hopes of burgeoning all too modest future growth predictions for both company and country have become all the more promising.

New government signals an improvement in fortunes for SQM

Despite a rocky recent past, it seems SQM may finally be able to take advantage of this window of opportunity, having reached reconciliation in their dispute with CORFO. The relationship between the two has been sour since 2014, when the allegation that SQM was exporting part of its potash production in Chile to a sister company abroad at a lower than market price led to a dispute over unpaid royalties, with CORFO claiming that SQM has failed to fulfil its lease obligations for CORFO’s Atacama properties. In more recent years, a crucial condition for reconciliation for CORFO has become a change in leadership within SQM – most notably former SQM chairman Julio Ponce Lerou, who has become emblematic of an allegedly dubious corporate culture within SQM; the rumours of which have inhibited CORFO’s ability to trust SQM to act equitably and agreeably towards their partners. Such rumours did not exclusively originate with Ponce, but CORFO may nonetheless assume that his complete departure will demonstrate a capitulation and willingness to compromise from an implied shift in culture within the company.

Adding greater urgency to the reconciliation process, SQM had recently announced plans to increase annual production at the Salar de Atacama from 48 to 63 kt LCE – an expansion that threatens to bring the date of their production quota running out as early as 2023. As is, SQM has been denied a proposal to double its production quota at Atacama and has had to resort to expansions outside of Chile, namely joint ventures in the Cauchari-Olaroz lithium brine project in Jujuy, Argentina and a hard rock project in Mt. Holland, Australia, to maintain production volumes and preserve to some extent, its status as a leading lithium producer.

The deal, well-timed as it is, is no coincidence; no doubt those in Chile have been keen to take advantage of the lithium boom as Australia has been, but the process may have been expedited by the election of Sebastián Piñera on the 18th of December – the same day as the suspension of the arbitration process between CORFO ad SQM. Piñera has been linked to SQM in the past – accusations of irregular practices were made toward the end of his last term in 2014, stemming from allegations of illicit political campaigning from SQM during his 2010 election campaign. In the run up to the election, Piñera expressed his support for CORFO’s vice president, Eduardo Bitran, acknowledging that Bitran was defending the best interests of Chile, but nonetheless still faced media scrutiny over his relationship with SQM. For all parties involved, then, a settlement before his swearing in on the 11th March was preferable; it enables the outgoing government to safeguard their legacy from accusations of obstructionism, and allows SQM and Piñera to avoid media speculation over whether the deal was reached through similar illicit processes.

SQM may have agreed to pay $17.5m to CORFO, as well as between $10 and $15m in royalties a year, depending on the price of lithium, but in return are licenced to extract 349,553 tonnes of lithium metal until 2030 – a staggering 1.9 million tonnes LCE that translates to roughly 107kt p/y, on top of the current capacity of 48kt p/y, given a year to commence production. A 25% production share will be set aside to be sold at lower prices to a nascent value-adding industry within Chile.

The potential ramifications of such an increase are already causing some concern - SQM now has the option to produce 170kt p/y by 2020, which would represent over 40% of CRU’s forecast demand of 408kt p/y in the same year. Should such a substantial increase in supply come to fruition, it would flood the market, causing prices to plummet; a worrying prospect for fellow producers. But anxieties are misplaced: brine operations require a high capital expenditure to set up and a large amount of land, meaning Atacama is unlikely to expand with the speed seen by, for example, Australian hard rock projects; regardless, even though SQM’s Atacama project might have some of the lowest operating costs of any lithium project (perhaps, once economies of scale have been factored in with the new expansion, the ), it is certainly not in their interest to spend heavily in expanding production only to reduce their profits. A relatively smaller capacity increase factoring in increasing demand is more likely, allowing SQM to command a controlling share of global supply in the long term; this will mainly affect small-scale hard rock operations on the high end of the cost curve.

There is also the further question of SQM’s holdings outside Chile. Whilst the project at Cuachari-Olaroz may be too advanced to terminate, given that it is projected to come online next year, it is unlikely that SQM will choose to expend resources on their comparatively less profitable hard rock venture in Mt Holland, which is still a number of years from opening; instead, it is likely that resources will be diverted back to Chile to facilitate expansion at the Salar de Atacama.

Most immediately apparent will be the effect to SQM’s share value. The prospect of global oversupply precipitating from this increase could cause a dip, but in the long term SQM’s shareholders will benefit from the higher output levels. This is most crucial for the 32% stake that Potash Corp is in the process of divesting. Uncertainty over the resolution of the conflict has caused potential bidders to proceed with caution and, in the case of Rio Tinto, even remove themselves from the running, but whoever wins the bid will now need to have considerable financial strength for the acquisition. Companies rumoured to be bidding include the Chinese battery manufacturer Ningbo Shanshan Co., the Canadian mining company Wealth Minerals, Tianqi Lithium Industries, and the Chinese hedge fund manager GSR.

These companies will be weighing up the increased cost against the greater likelihood of financial payoff in the coming years, as well as further benefits dependant on the acquirer’s position on the Li-ion battery value chain. For fellow miners such as Tianqi and Wealth Minerals, the tender represents the potential for horizontal integration, diversification and a consolidation of market share – indeed, CRU expects there to be some resistance to bids from the likes of Tianqi and Albermarle due to concerns over market concentration. Should the winning bid come from downstream, then – from Ningbo Shanshan or GSR, who bought Nissan’s battery business in 2017 for $1 billion – there is the opportunity to ensure resource security and streamline the supply chain. It is also worth noting that SQM is a very large player not only in lithium, but also other products extracted from brines, such as potash, offering prospective buyers exposure to other markets.

Interest in a value adding industry further helps Chilean prospects

Chile’s wider lithium industry will also benefit from the deal, as the discretionary 25% promised to local industry will ensure cheap supply for national projects. As CRU has recently explored, the limiting factor in the global lithium market is the timing mismatch of low long it takes to commission a new capacity at each stage of the value chain; this will create long lead times for the production of battery quality chemicals, and may even limit supply reaching end users. The Chilean government, however, have demonstrated an interest in bringing new downstream processing capacity to bear within Chile, maximising the value of their national minerals. The news broke last month that CORFO’s tender for the establishment of a value-adding lithium industry had produced a shortlist of seven proposals, later dropping to six: three Chinese, one Russian, one Korean and one local firm, the majority of which concerned the production and manufacture of metallic lithium and lithium cathode material for electric car batteries. SQM’s new deals offers assurance of supply for these companies, potentially increasing both the value of the tender and interest in it; this could potentially lead to new industry receiving a significant investment right off the bat.

The emergence of a more value adding lithium industry within Chile would, in turn, benefit Chile. The Atacama salt flats may provide an abundant source of lithium carbonate at a low cost, but unlike hard rock deposits elsewhere in the world, brine products typically contain high levels of impurities.

Converting lithium carbonate to lithium hydroxide is also a necessary additional process for brine producers that incurs additional expenses, but lithium extraction projects at the Salar de Atacama have sufficiently low overheads to allow them to do so; whilst this may reduce profit margins, it would ensure Chile remains competitive in a future where consumers require increasing amounts of hydroxide. Moreover, any new industry is unlikely to remain untouched by the growing trend of supply chain integration seen in the lithium industry, and SQM will benefit from even closer collaboration, shorter lead times and lower shipping costs stemming from such close proximity to downsteam capacities.

The future, then, looks bright for both nation and company. The rift between SQM and the Chilean government has led to a stagnation in growth to the detriment of both parties involved, which has been one of the factors (along with strict regulations and classification of lithium as a “strategic mineral”) that has contributed to the country’s weak project pipeline. But reconciliation will bolster growth; SQM, having made preparations for continued arbitration by expanding to Cauchari-Olaroz, can now expect robust growth both within and without Chile; likewise, with the new year comes a renewed optimism for investors in Chilean lithium, who are now in a good position to reap the benefit of the impending boom in demand.