Environmental policy and regulation is creating long term risks to thermal coal demand, particularly in Europe and other advanced economies. Critically, as explored in this Insight, this is also directly re-shaping the regulatory environment for future coal mining projects.

Recent developments in the Australian courts affecting approval of new thermal coal projects could spell serious consequences, particularly for owners of moderate and low energy density coal resources. How will makers respond in the face of collapsing investment?

The regulatory context post-Rocky Hill mine refusal

In February 2019, the New South Wales (NSW) Land and Environment Court refused consent to a proposed Rocky Hill coal mine. The judgment rested heavily on scientific testament regarding the impact of the project on environmental and climate outcomes, and the purported potential for a rapid shift to cleaner forms of steel production. In effect, this judgment indicated that greenhouse gas (GHG) impacts have the potential to decisively shape coal mining project approvals.

While the Rocky Hill case does not set a formal legal precedent, the central arguments used are likely to have broader applicability to other cases. This is in evidence, for example, from the more recent approval process relating to United Wambo, a Glencore-Peabody joint venture open pit (largely thermal) coal project in New South Wales.

Following in the spirit of the Roy Hill decision, the Independent Planning Commission (IPC) required an evaluation not only of scope 1 and 2, but also, critically, scope 3 emissions (those associated with the transportation and combustion of the product) as part of the project permitting. CRU has engaged to analyse these full chain impacts. Our work identifies potentially critical risks for the future of low energy density coal projects

Long term risks to thermal coal demand on the horizon

Thermal coal remains a central means by which the world’s power needs are met. More than 2,000 GW of coal-fired power stations have been installed around the world, and some additional growth is expected in the years ahead, particularly in Asia. As such, CRU’s base case is for relatively stable long-term thermal coal demand.

That said, thermal coal’s position is increasingly under threat, particularly in regions such as Europe and the US. CRU’s base case already factors in current and some future policies to curb emissions. However, rising concerns regarding climate change, and related policy and investment responses, could expose more serious downside risks to this central case.

What if Western exporters exit the seaborne market?

CRU has evaluated the GHG impacts of a refusal by the IPC to approve the United Wambo project. This was based on a rigorous analysis of the alternative supply sources. In this context, our work focussed on a number of Central, South and South East Asian countries, such as Russia, China, India and Indonesia, which have large coal industries that are well placed to serve unmet demand.

CRU compared the costs and investment pipelines to form a robust view of the alternative supply picture in the absence of continued Australia coal sector development. Our approach comparing different supply sources on a “like for like” value basis, considering the costs of producing, processing and shipping coal of different qualities into major demand hubs. Figures 2 provides a high-level overview of average delivered costs respectively by coal market. Our analysis highlighted the projected competitiveness of alternative supply sources such as Indonesia, China and Russia.

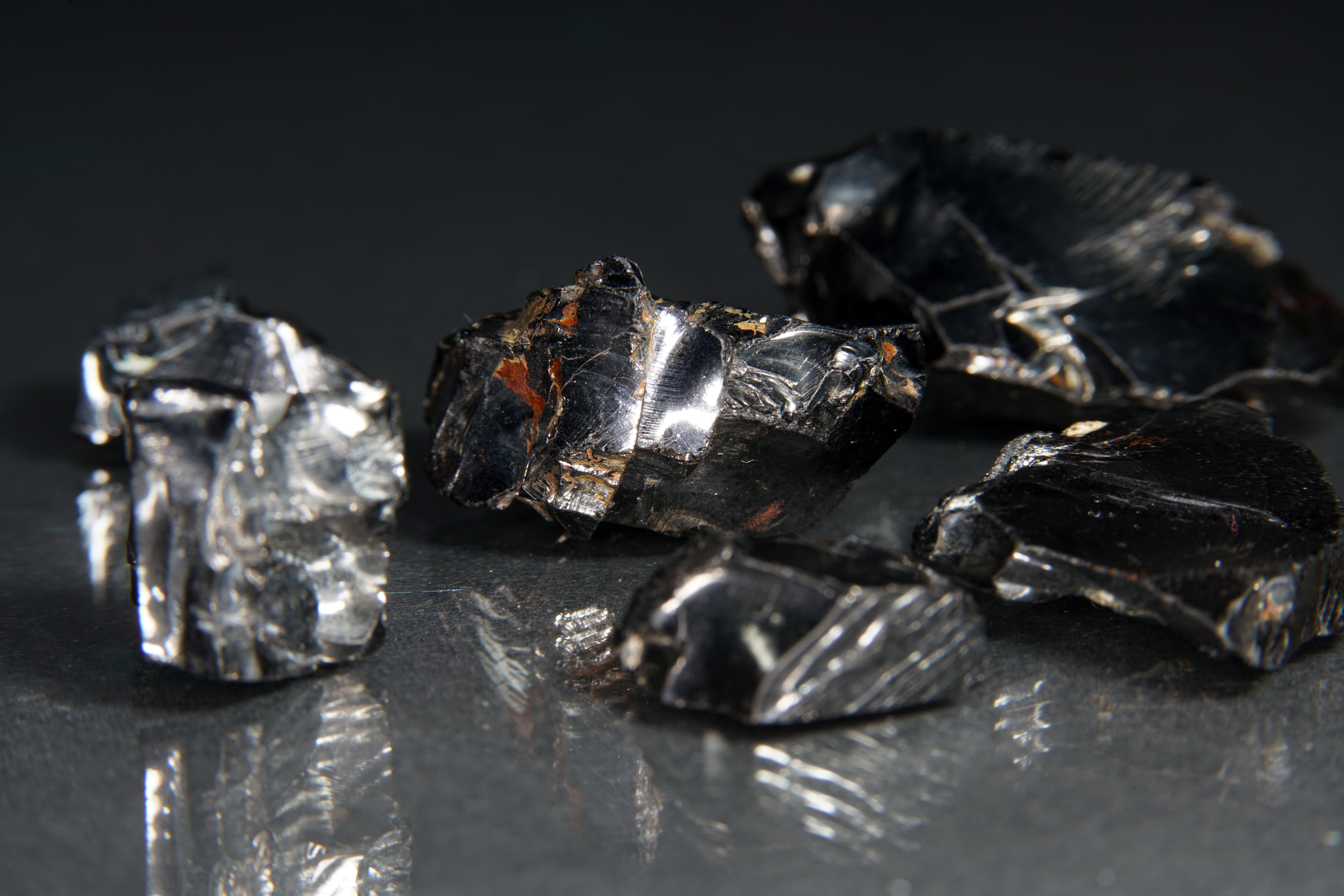

Coal quality key to net GHG impacts of a project approval

Comparing the energy densities of coal produced in different jurisdictions is key to understanding the full chain GHG impacts of a project approval. It is important to consider the different calorific values around the world because high energy coal would need to be replaced by combustion of a disproportionate amount of low energy coal – and thus GHG emissions – in order to generate the same amount of power. Overall, for example, the energy stored in 1t of average Australian coal requires 0.97 – 1.23t of coal from alternative countries, depending on their average energy density to deliver the same power. This is shown in Figure 3.

Energy density a key determinant of export market access

The United Wambo project was approved, subject to conditions, in September 2019. CRU’s analysis showed that the high energy density nature of the coal produced by United Wambo meant that overall GHG emissions – considering scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions – would rise (by in the order of 1-280 MT depending on the regulatory scenario) were the project (or indeed the wider Australian thermal coal sector) not approved and supply met from major Asian coal industries. However, the development of low-energy density coal would not have been supported by CRU’s analysis.

A growing risk of stranded assets, how will policy makers respond to collapsing investment?

A transformation in energy markets is underway and brings long term risks to thermal coal supply, not just indirectly through constrained demand but also through regulations affecting new projects. Recent developments in the permitting process affecting new thermal coal projects in NSW Australia are potentially indicative of a shifting regulatory environment and could spell serious consequences, particularly for owners of moderate and low energy density coal resources.

CRU’s analysis shows that this could potentially lock out export growth in low energy density coal. These issues could deepen in the event of the expansion of these regulatory developments to new jurisdictions and new value chains, and, if the rather weak conditions imposed on project developers – including the requirement to sign offtake agreements with Paris signatories (rather than, say, effective implementers of climate polices) – become tighter.

Evaluating and adapting to these risks will not be straightforward for many firms and operations and will expose investors to new risks. It is further complicated by potential reactions by local governments to the adverse effects of collapsing mining sector investment. In NSW, for example, the government are proposing new legislation to curb the ability of the IPC to make judgements based on international emissions. Will such counter measures be successful?

These issues require a deeper understanding of a range of issues including the outlook for regulatory change in key jurisdictions, the nature of potential carbon substitution effects and their implications for future asset values and cash flows at both a firm and sector level.