India is expected to enter recession following the quarantine imposed on the world’s second most populous country.

The recent plunge in the PMI activity index highlights the huge economic costs of lockdown. But the worst is yet to come. We expect GDP growth to contract by 0.9% in 2020, well below the 7% norm of recent years. Risks are numerous should the accumulated structural weakness backfire during this unprecedented crisis.

Recession peaks as consumption troughs

As the world pressed the “pause” button by imposing lockdowns, growth has been brought to a halt. India is no exception. A recession is now expected in the subcontinent in 2020. We currently forecast Indian GDP growth to contract by 0.9% y/y in 2020, compared with our forecast of growth of 4% y/y in March. We have sharply cut the forecast published in our April report as a result of (i) the general lockdown from March 25, limiting the movement of 1.3 billion people, and (ii) the weak overall government response amidst intrinsic structural economic weaknesses in India.

Before the lockdown we had expected GDP to grow at 4% y/y in 2020 and to drop to 2.9% y/y in Q2. This was driven by a reduction in fixed investment and stock-building (Figure 1). However, since the “stay-at-home” orders have been put into effect, and now extended to May 17, we expect consumption growth to be much weaker. This is because lockdowns are preventing households from spending. Investment is also expected to make a negative contribution to GDP growth, as companies face a large degree of uncertainty about the future and so delay or cancel investment projects.

We now expect a contraction of 4.3% y/y in GDP in Q2, and 1.36% y/y in Q3. These quarterly contractions would be the worst since such official data were released in the early 1990s. A return to growth is likely in the last quarter of 2020 followed by a strong recovery in 2021 at 7.6%. This recession should be U-shaped since we expect a return to trend growth rates within a year but a permanent loss in the level of output (see our Insight, V, U, L – Demystifying recession shapes for more details).

The latest IHS Markit manufacturing PMI dropped to a record low of 27.4 from 51.8 a month earlier. Similarly, services PMI plunged to 5.4 from 49.1 in March. For both surveys, these are the sharpest decreases since IHS Markit started the series 15 years ago. PMI is a high frequency indicator which gives a general picture of the health of an economy. Thus, a sharp decline in the April PMI indicates a sharp drop in output in Q2. This supports our figures. We forecast Industrial Production (IP) to be around -12% y/y in Q2 and on average to fall by 3% y/y in 2020.

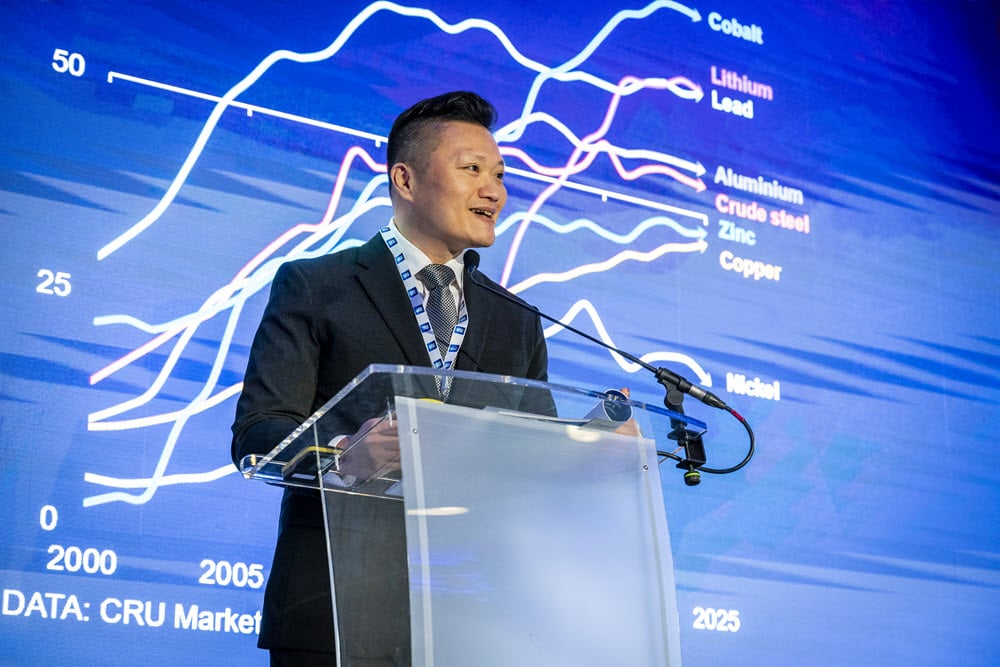

The metal-intensive sector will be severely hurt. We foresee largescale disruption to India’s 2020 car market: production of light vehicles is likely to fall by more than 500,000 units; car sales are expected to fall by more than 1 million units. This cut in auto production is unprecedented; no such drop happened during the global financial crisis. Vehicle registration in April 2020 reduced by 80% y/y. Moreover, we expect a recovery in car production to its 2019 levels by the end of 2021 (Watch our webcast: How is the lockdown affecting the Indian fertilizers and metals industry?).

Supply chains open as restrictions ease to some extent

The Indian government has allowed industrial activity to start on a limited basis in certain locations. For this purpose, the government has divided the 700+ districts in India into green, orange and red zones and guidelines have been issued to restart activity based on these classifications. This list will be reviewed weekly and will be based on the growth of Covid-19 cases in each district.

Many industrial units have been given permission to restart activity; however, this is at low capacity utilisation. There are concerns about labour availability as well because many of migrant workers (who constitute a significant portion of the labour force) have returned home and are unlikely to come back until the situation normalises.

Modest policy response, bolder measures expected

The announced fiscal and monetary stimulus measures will provide some support to the economy. However, given the size of the coming recession, it does not appear to be sufficient to put India back on its pre-Covid-19 growth path. In our forecast, we assume that more will be offered.

The RBI cut the repo rate by 75bps to 4.4% from 5.15% - a massive cut and the lowest interest rate in Indian history. The bank will also inject 3.7 trillion rupees of liquidity into the banking system, offer a 3-months moratorium on interest payments and ease liquidity thanks to targeted long-term repo operations.

The government’s fiscal package of 0.8% of GDP announced on March 26 is relatively modest compared to other countries. To give an example, the US has offered a package of 11% of GDP, Eurozone around 3% and China 1.6%, and all three major regions are expected to do more. The key elements of the Indian stimulus package are cash and in-kind (such as food) transfers to poor households, income protection insurance and a benefits scheme for both low-wage workers and the unemployed. However, the government will have to offer more if it wants to prevent the recession from extending into 2021. One explanation for this modest fiscal stimulus is that the public finances are already stretched, and this has tied the hands of Finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman. However, we believe the government has some hidden cards in its pocket, ready to be played. A new fiscal package is expected soon.

Structural factors are an underlying risk to India’s outlook

There is great uncertainty surrounding all our macro forecasts at present. These arise from uncertainty about the duration of the lockdown, the spread of the virus and the government policy response. But for India, there is an additional risk, that relates to the structural weaknesses of its financial sector. Should that deteriorate it could worsen access to credit, lowering private sector expenditure and therefore GDP growth. There is some evidence that the degree of caution from the financial sector is increasing. For example, bank non-performing loans (NPL) are expected to rise, which also reduces funding offered by the non-bank financial sector. Similarly, the approved rescue plan of Yes Bank in March acted to undermine views about the resilience of the financial sector.

Low demand, weak infrastructure and a troubled financial sector are three long-lasting issues which are holding back growth in India. The virus outbreak exposed these vulnerabilities further. Covid-19 risks being the ‘straw that breaks the camel’s back’.