China’s real estate market has grown rapidly in the past 25 years and is a key pillar of the economy. It is also a key source of demand for commodities, in particular steel, aluminium, and copper.

We have seen the property market ebb and flow; for example, the exuberance of 2016 and deflation of the bubble in 2017. Looking forward, will China’s property market sustain its miraculous growth? How will the government interventions shape the outlook for property markets? Most importantly, how will they impact commodity markets?

China’s construction sector is a huge consumer of metals

The construction sector is the single most important end-use sector in China as it directly consumes a significant proportion of metals: 56% of steel, 49% of aluminium, and 41% of copper (Figure 2). In addition, other end-use sectors, such as household appliances and power grid distribution, are directly connected to construction activity in the real estate markets. Given the large share of global demand China accounts for in metals markets, the Chinese construction sector is important for metals producers all around the world. While residential real estate is not the only driver of construction – commercial and industrial real estate, and infrastructure are also important – it is an important one.

Understanding China’s construction cycle therefore helps us forecast the timing of demand for metals. The beginning of the cycle can be characterised as a period with strong new starts, relatively weak completions, and relatively strong demand for steel products. The end phase of the construction cycle tends to exhibit weak new starts, relatively strong completions, and relatively strong demand for copper and aluminium (Figure 3).

Short run factors

The response to, and recovery from, the pandemic have shaped the behaviour of construction over the last year. Going forward, government policy towards real estate will look to balance financial stability with maintaining economic growth. This should lead to a moderation in construction growth.

Covid-19 Stimulus Measures

Policy has been an important driver of the property cycle in China. Each time the economy slows, the property sector is among the first resorts for the government to boost economic growth. But this can quickly lead to over-optimistic expectations, speculators rushing in and pushing up prices, and herding behaviours of rigid-demand buyers worsened the whole situation until tightened policies are finally enforced.

For example, China's real estate market declined sharply due to the lockdown that hit the sector from both the supply and the demand side. To combat the negative impact on the property sector, the Chinese authorities took actions to accelerate the implementation of Rural Land Policy Reform in which local governments are given more autonomy to approve construction in permanent cropland subject to stricter regulations, as well as to convert other farmlands into lands for development. These policies resulted in more land supply for construction, thus increasing the revenue of the local governments (Figure 6). Besides the land reform, the Chinese government made substantial efforts to provide liquidity to the real economy. To mitigate the financial market volatility and to ensure a sustainable credit flow to the real economy, in the beginning of February China's central bank pumped RMB1.2tn into the financial market. However, policy has now switched attention to trying to limit financial risks building up in the real estate sector.

Real estate investment

Individual Chinese investors have historically had access to a limited range of wealth management products offered by banks. This makes housing an attractive asset in many people’s minds – it is widely viewed as ‘risk-free but high return’. Home prices have risen substantially despite several rounds of crackdowns on housing speculation by central and local governments. Although mortgage rates are consistently higher than the return of alternative financial assets, home prices have often appreciated over 10% on an annual basis, and so the net return of real estate properties can still outpace investment returns of most other any other existing assets. However, real estate investment has softened as investors are now getting into the public markets through managed funds as well as passive ETFs to diversify away from real estate speculative risks (Figure 5).

As a result, household debt appears to have stabilised relative to deposits (Figure 6). We expect the trend to continue as the government relentlessly emphasised that ‘houses are for living in, not for speculation’.

Policy measures to cool the market

That said, the authorities are still concerned that the real estate market could lead to dangerous levels of leverage building up in other areas of the economy, such as construction firms or the banks that lend to them. For this reason, the government has set out a series of policies – the ‘three red lines’ (Table 1) – to cool the market and limit the build-up of risk. In the immediate term, this may have the perverse effect of boosting completions relative to starts, as developers accelerate their pipeline of work to boost their cash positions. Further out it is likely to limit construction activity. Furthermore, fiscal and monetary policy continue to move towards ‘normalisation’, which will limit infrastructure spending relative to the surge in 2020, as well as credit growth. (Content accessible to CRU Subscribers only)

Medium term factors: China’s 14th Five Year Plan (FYP)

The 14th Five Year Plan (CRU Subscriber access only) set out in March 2021 will be an important influence on the construction sector in China. It will impact the real estate and construction sectors in several ways:

Dual Circulation

Dual Circulation is one of the major themes set out in China’s14th FYP. To facilitate the ‘internal circulation’, China needs to boost household incomes and rebalance investment and consumption by curbing excessive investment and redirecting more resources to social spending to support emerging social safety nets. As such, Chinese authorities will continue to focus on economic restructuring, property destocking and initiating reforms on deleveraging, as well as greater control over access to property financing. Additionally, we expect household saving will be re-directed from real estate investment to consumption (Figure 6).

Urbanisation and Hukou Reform

China aims to achieve a 65% urbanisation rate during the 14th FYP period. Interestingly, the recent census showed that urbanisation has accelerated faster over the past decade than indicated by official statistics and mainstream estimates. The census found that in 2020 there were 902mn people living in urban areas, or 63.9% of the population. This is substantially higher than the National Bureau of Statistics’ own pre-census estimates, which had put the urbanisation rate at 60.6%.

The 14th FYP outlines a further loosening of the household registration system (‘hukou’) policy even for China’s largest cities. The implication of this policy is that it will be easier, both for the rural population and for the non-hukou migrants, to gain access to the hukou benefits. Previous liberalisation of hukou policy may help explain the urbanisation surprise as well as the surprising resilience in China’s housing demand in recent years.

Looking ahead, we expect a continual flow of internal migrants as the government authorities reduce the barriers to rural-urban migration. China’s urban housing markets in the southern region in particular will have to accommodate almost 20mn more new residents in the coming decade (Figure 7).

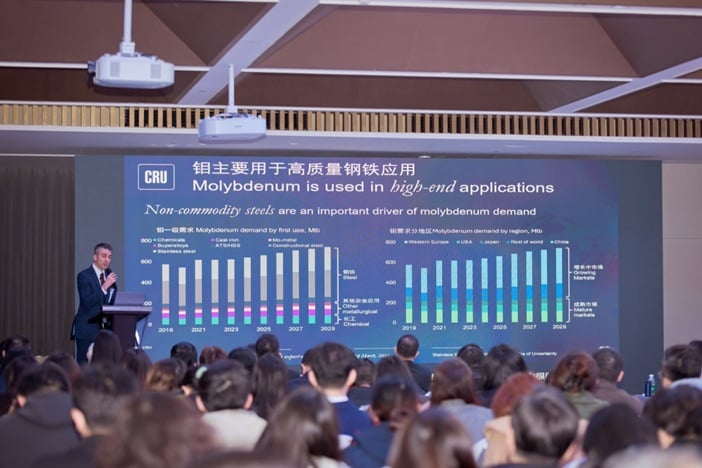

Decarbonisation

China has committed to carbon dioxide emissions peaking by 2030, and to achieving carbon neutrality by 2060. China's building-material and construction sectors generate over half of the country's carbon emissions, and China's efforts to cut carbon emissions will have major implications for the industry.

While green building still makes up a small proportion of China’s construction industry, we expect that the number of green building projects will grow rapidly and will account for 70% of new urban building by 2022 (Figure 8). The rise of green construction will have complicated impacts on input demand which will vary across different materials. For example, there will be pressure to economise on steel and cement as building materials, given their high carbon footprint. However, promotion of home/work charging and renewable power could increase demand for copper.

Long-run factors

In the long-run, demand for Chinese real estate will be driven by demographics, urbanisation and average desired floorspace per person. CRU’s long-run model analyses all of these factors. It suggests that completions will soon peak in China, and then decline as the market matures. However, replacement demand will still require a large volume of metals.

Population growth

Historically, favourable demographics and rapid urbanisation have been the main driving forces behind the real estate construction boom in China. However, according to the 2020 census, China’s population has been growing more slowly than generally thought. Along with a slowing population growth rate, the census data also revealed that the number of first-time housing buyers peaked in 2017. In addition, the growth of the labour force and the urban population continued the downward trend seen since 2000, which represents long-term structural headwinds for China’s real estate market (Figure 9).

Features of the CRU floor space model

CRU have a proprietary model of urban floor space in China that incorporates developments in urbanization and population density. The model also takes account of implications for living space per household. With this framework, we can show that while annual increments of new Chinese floorspace will fall over time, there is some support from a growing number of smaller households.

In addition, the model considers the fact that a third of Chinese urban residential completions are expected to be replacements for existing buildings. Many historical Chinese urban residential buildings are inadequate for their residents and will be demolished and replaced with better housing. CRU has chosen a methodology to measure the impact of replacement that takes account of the special features of the Chinese housing booms, namely that they have occurred in large bursts, that survival lifetimes are expected to be distributed and are lengthening as time goes on.

Discover the new floor space model in depth -

speak to our economics team

Lastly, our model takes account of the reclassification process as Chinese cities have grown by absorbing their surrounding rural areas. The more reclassification that occurs, the less urban construction is needed.

What the model says about future completions

While the residential real estate market will inevitably slow down, we think that there will be a further large bulge in Chinese construction due to the replacement of 1980s housing stock (Figure 10). In comparison with our previous long-term forecast, we expect that there will be even more replacement during this period, as according to our calculations some replacement that should have taken place in 2016 to 2020 has been postponed.

We expect residential completions to peak at 3713 million metres squared in 2022. Beyond the mid-2020s, Chinese urban floorspace completions will slow down. As mentioned above, this is simply because the market will become saturated and because China’s population declines. The more building that takes place now, the less is needed in the future, and therefore the steeper the deceleration from 2022 onwards. In the more distant future, the Chinese construction sector settles into being a mature market where replacement dominates demand. Given the size of the stock, replacement will still be a large source of demand for metals.

The balance of risks

Though the current policy environment has imposed tightening pressures on the residential property market, these pressures should be manageable. Much of the stimulating policies to combat the impact of Covid-19 were used to meet liquidity needs, rather than to build infrastructure or buy property as was the case with the GFC stimulus.

That does not, however, negate the increased risk of individual defaults. The biggest risks are to those unable to refinance in a tightening credit environment, particularly the credit-hungry property sector. As the tide of stimulus recedes, real estate and construction developers will need to be increasingly selective about the projects they develop.

In the longer term, powerful forces of demographics and satiation will limit demand. Even if the replacement demands for residential building is indeed realised, the wider story of China’s gradual economic slowdown remain unchanged. While construction activity has remained robust in early 2021, it will eventually slow over the coming years and decades. Table 2 summarises the key short, medium and long-term risks set out in this Insight.