On the 22 October 2020, the South African government announced they were considering a chrome ore tax, in a stated attempt to protect the domestic ferrochrome industry and entire chrome value chain. While the tax has been mooted in previous years, the challenging long-term prospects of the domestic FeCr industry has become more apparent in recent years because of increasing electricity costs.

A further 15% increase in electricity tariffs by South Africa’s utility provider, Eskom, in 2021 as well as all FeCr smelters putting out Section 189 redundancy consultations during 2020 forced the issue to the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy (DMRE). While a chrome ore tax does protect South African smelting interests, the benefits could be negated by a retaliation from China or cost pressures for conventional miners.

Alloy supported, but at what cost?

The proposed export tax on South African chrome ore is designed to support domestic FeCr production and its entire chrome value chain. The plight of the domestic smelting industry has persuaded the government to revisit the tax on chrome ore exports, which it is hoped will make domestic capacity more competitive against their Chinese counterparts. Chinese growing use of by-product UG2 chrome ore and the rapidly increasing electricity tariffs in South Africa have supported the development of FeCr smelting capacity in China. The impact of this proposed tax will increase smelting costs in China, tipping them in favour of South African smelters. The tax could slowly erode global market share for South Africa’s conventional chromite miners over the long term, as it will make them less competitive on a global basis.

An export tax could push certain, high cost South African conventional ore producers towards the higher end of the cost curve towards average costs in Turkey or Zimbabwe. It is important to remember however, that even with a tax, South Africa will remain dominant in the chrome ore market for the foreseeable future due to the scale of its resources.

Longer term, the tax could shift mine investments away from South Africa. We could see Chinese operators becoming even more global with their investments, in line with their belt and road strategy. In the near term, Turkey and Zimbabwe will not be able to ramp up to meet demand levels in China and elsewhere, and significant further investment is needed if they were to. Chinese companies could look at investments in these nations to increase capacity and provide chrome ore competitively to Chinese owned smelters, although South Africa has by far the largest chromite reserves globally. Zimbabwe is the second-place contender and foreign direct investment over the years could develop its chrome mining sector. Yet it would take massive investment and many years for mining in Zimbabwe to significantly displace South African ore volumes.

Even if the tax is implemented, South Africa will remain dominant in the chrome ore market, meaning that South African chromite will continue to form a large baseline of global supply. The tax offers South Africa a new source of revenue, which in turn could help ease Eskom’s growing debt pile.

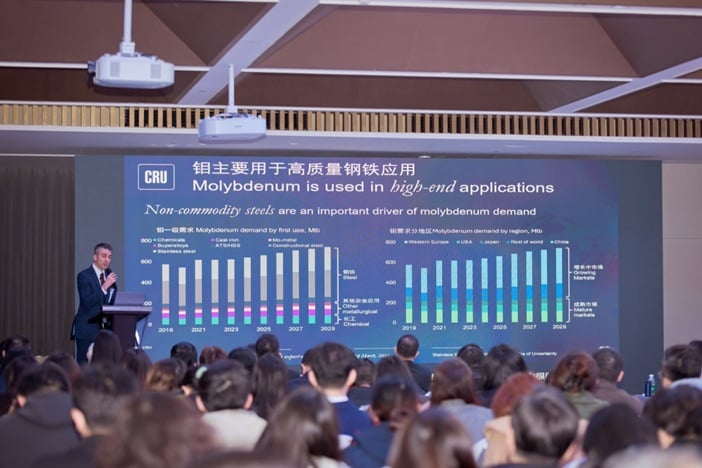

China to feel the impact

The impact of a tax on ore will inevitably raise smelting costs globally but particularly in China, as they are reliant on South African ore imports. In 2020, 82% or 11.7 Mt of China’s total chrome ore imports were of South African origin. Chinese smelting costs are heavily influenced by the price of chrome ore, whilst for South Africa energy is the key driver. Increasing costs at Chinese smelters would lead to lower production, particularly in Southern China, where costs are higher. In turn this could lead to more Chinese imports of FeCr from South Africa, a positive for smelters there.

There is a risk that China may not let this happen without some form of retaliatory action. The reported ban on Australian met and thermal coal in late-2020 shows that China is not afraid to use the commodity trade to protect its interests, although this example was politically focused. China has invested heavily to become more self-reliant within the stainless value chain and could act to defend this position, at least for its own domestic requirements. Recent energy controls impacting Chinese smelters, and the closure of smaller more polluting furnaces, may signal that a retaliatory response is becoming less likely.

Long term issues not fully addressed

Electricity tariffs from Eskom have increased by more than 500% (in ZAR terms) over the last ten years to large industrial customers. This has hit their global competitiveness, for example we have seen the closure or mothballing of over 40% of South Africa’s ferroalloy capacity. A further 15% hike in tariffs has been approved for 2021, with additional increases expected in 2022 and beyond. The critical component of smelting competitiveness is the availability of a cost-effective and reliable electricity supply. The proposed tax on chrome ore may not save South Africa’s ferroalloy smelting industry in the long run if significantly higher energy costs materialise. Ultimately, any relative cost gains due to a chrome ore tax could be eroded over the next few years if energy tariffs in South Africa continue to rise sharply. This would make the mooted benefits from any export tax unsustainable.

The market currently awaits further clarity from the South African government. We understand that groups supporting the plans are lobbying for the implementation of the tax to be expediated whilst opposing groups have been rejected from gaining exemption by the Competition Commission, highlighting fiercely conflicting interests within the industry. With conventional miners resisting any attempts at imposing the tax, the road to imposition could be long and unclear. Any ore tax will shift the global cost curve, putting Chinese smelting under pressure at a time when energy tariffs there are also rising. In the medium to long term, increased investment in chromium mining, and even FeCr smelting, in countries like Zimbabwe could gradually chip away at South Africa’s market share.