The world is attempting to shift away from a fossil fuel energy system to a materials-intensive renewable energy system, but the raw material markets vital for mass deployment of renewables face a range of challenges. The coming decades will see vastly more competition for the materials needed for the green transition. Asia will be at the centre of this.

Electricity systems are where the most rapid change is expected, as we have the technologies needed to decarbonise the grid and electricity is the lynchpin of a green economy. Decarbonising other sectors often relies on electrification of fossil fuel processes or electrolytically produced feedstocks, such as hydrogen. Mass decarbonisation, which is needed to hit the Paris agreement aims, cannot happen unless we invest in grids and renewable generation.

Asia is central to renewable energy markets

Energy systems across Asia will rapidly change over the coming decades, with the transformation being at a pace not previously seen in human history. This will be led by huge growth in solar and wind capacity, by 2050 CRU expects 55% of all solar and wind installations will have taken place in Asia.

China is central to this story, both because of its huge domestic power requirement and vast manufacturing base. China has already installed ~750 GW of solar and wind (n.b. ~40% of the cumulative global total), as well as over 400 GW of hydro capacity. Indeed, CRU forecasts Chinese renewable installations will surpass the government’s commitments and, by 2030, we expect Chinese installed capacity of wind and solar will reach ~1,650 GW, about a third above the government target.

The Chinese government has committed to carbon neutrality by 2060, which will require huge additional solar and wind installations and we forecast capacity will hit over 4,300 GW by 2050. This will take a monumental quantity of raw materials and will test supply chains globally. However, China’s ability to deploy at scale should no longer surprise us.

Yet, risks remain. The Chinese central government released a raft of financial support and obligatory targets to drive renewable energy, but it also removed many subsidies in 2021. Moreover, coal has seen a resurgence this year and will remain vital in China’s energy mix for at least the next two decades.

Japan is aiming for carbon neutrality by 2050. By 2030, the Japanese government has previously pledged to increase the share of solar power to 14–16%, from 2.7% today, and wind power to 5%, from 0.8% today. South Korea has made pledges to increase renewable generation to 20% of the power mix by 2030, with offshore wind a focus. While these targets are modest, the country is also increasing nuclear output.

India is a market with huge potential, a vast population and pent-up demand and the government has pledged to take non-fossil energy capacity to 500 GW and for 50% of its electricity requirements to come from renewables by 2030. However, given current rates of change, India’s pledges are challenging.

Elsewhere in Asia, the lack of carbon prices/costs will keep fossil fuels competitive with renewables. However, there will be regional variation and subsidies will play a role. For example, Vietnam has driven large solar capacity additions through feed-in tariff schemes and, across Asia, ‘Just Energy Transition Partnerships’ and financial support are building momentum. Yet, installing so much capacity, not just in Asia but globally, in such a short time will be challenging for the region and commodity markets will be tested.

Managing price risk in volatile markets will be vital

Metals demand will be shaped by the energy transition, but applications will also be shaped by materials pricing. Historically, metal costs accounted for 7–15% of upfront capex. costs, this will be higher in the future.

Commodities prices rose to very high levels in 2022 and, even though some have seen substantial declines, they remain high. Many commodities are likely to remain elevated into the medium term due to increased demand pressures. These will directly feed into higher costs for renewables.

Managing price risk in volatile markets will be vital. A good example is offshore wind, which requires large volumes of steel over long build periods. Steel is used for the tower, transition piece, offshore substation and, most importantly, the foundation. A monopile foundation is essentially a large steel tube driven into the seabed – supporting a large turbine out at sea presents a challenge for material strength and durability and steel plate provides an excellent solution to that challenge.

Steel prices are volatile and purchasing teams in offshore wind companies face the challenge of market timing or require complex risk management. CRU discovers plate prices globally, including across Asia, but the below chart shows a cautionary example of the volatility European plate consumers faced this year.

Almost all polysilicon for solar production is in China and, along with silver-paste, glass and frames, it is a key input cost for solar cells. Prices of polysilicon have increased hugely over the last two years. Prices are likely to come down, at least short term. However, this supply chain is becoming increasingly politicised, attracting the interest of policy makers globally which will have implications for solar module costs. Affordable solar photovoltaics will be crucial if Asian countries are to achieve their decarbonisation goals.

Wind and solar vital for copper demand growth…

Copper is used more intensively in renewables than in conventional generation and so solar and wind are vital for copper demand growth, although they are a relatively small part of today’s markets. CRU forecasts global copper consumption in solar and wind installations will double from 2020 to 2030, hitting 1.5 Mt. Huge grid enhancements are also needed, which will further boost copper demand. Along with demand growth from electric vehicles, growth of the global copper market is almost entirely contingent on a green transition.

… but supply gaps will need to be addressed

The copper industry is heading for a significant structural imbalance, causing a supply gap from the middle of this decade that will impact prices. We forecast over 6 Mt of mine production will need to be added to the copper market to meet projected demand in 10 years. Much of this is needed to power green technologies.

To incentivise new production coming online, copper prices will need to lift to levels where opening a new mine can be profitable. This price will need to cover more than just the cash operating costs if sufficient supply can be found. Copper mine constructions are large and complicated investments and higher prices may be needed if the market is to meet the needs of the energy transition.

Vast energy storage will be needed

A rising share of renewables will cause more variability in electricity supply and grid balancing will become more complex. In addition to improved grids, power storage systems will be needed to ensure the dispatch of electricity even when wind or solar generation is low. The true cost of renewables therefore needs to take account of power storage in the system.

With technological improvements, CRU believes variability can be managed and will not stop a significant roll out of new renewables capacity in the coming years. But the need for mass deployment of batteries for grid storage creates new supply chain risks.

Concentrated supply chains can increase risk

China currently plays an outsized role in raw material markets vital to wind and solar production. Chinese companies are even more dominant in battery material supply chains.

Concentrated supply chains can exist at the corporate as well as national level. Out of thousands of cable factories worldwide, only around 30 sites can currently produce subsea cable due to relatively high technical and capital entry barriers. For offshore wind, when including installation costs, wire and cables can account for almost 17% of the total project cost. This is due to the extensive usage of high-value subsea export and array cables and the sophisticated cable-laying works required by specialist vessels. Moreover, we foresee a clear challenge for subsea cable producers to meet such exceptional demand.

Geopolitics are also shaping supply chains

Beyond economic and market considerations, geopolitics and trade rules pose additional risks. For example, there are significant anti-dumping duties on Chinese products in the solar value chain in many global markets and countries. Moreover, the USA has brought in a raft of measures to boost domestic manufacturing and could remove China from the US solar supply chain altogether. Similar legislation could follow from other markets, such as the European Union.

Trade measures are also evident in Asia. India introduced import duties of 40% on solar modules and 25% on solar cells in April 2022. With ~80% of solar panels imported, mainly from China, this has led to higher costs and more limited availability of solar panels, and at least one large solar project has been put on hold. The new policy also only allows procurement of solar panels for government-funded projects from the approved list of mainly domestic suppliers, which have limited capacity. India is forecast to start polysilicon production in 2025.

Despite these policies, by 2026, CRU forecasts that China will still account for ~87% of polysilicon capacity with the rest coming from North America, Europe, North Asia and India.

Emissions will increasingly determine supply choices

Renewable developers looking to lower Scope 3 emissions need to source low-CO2 commodities. But decarbonising many commodity markets will be a huge task, requiring massive capital expenditure, process flowsheet change and sufficient supply of energy and raw materials. Understanding the nuances of emissions produced in commodity markers requires good data.

The roll out of electric vehicles and wind and solar power generation capacity will add over 10 Mt of aluminium consumption by the 2040s. Solar panels often use aluminium in installation brackets, although steel is mostly used for utility installations. Moreover, nearly all bare overhead cables are aluminium. Yet, aluminium is notoriously electricity intensive requiring an average of 14.2 MWh/t. To add to this complexity, CRU’s models show emissions from smelters can range from 2–20 tCO2e/t on a Scope 1 and 2 basis.

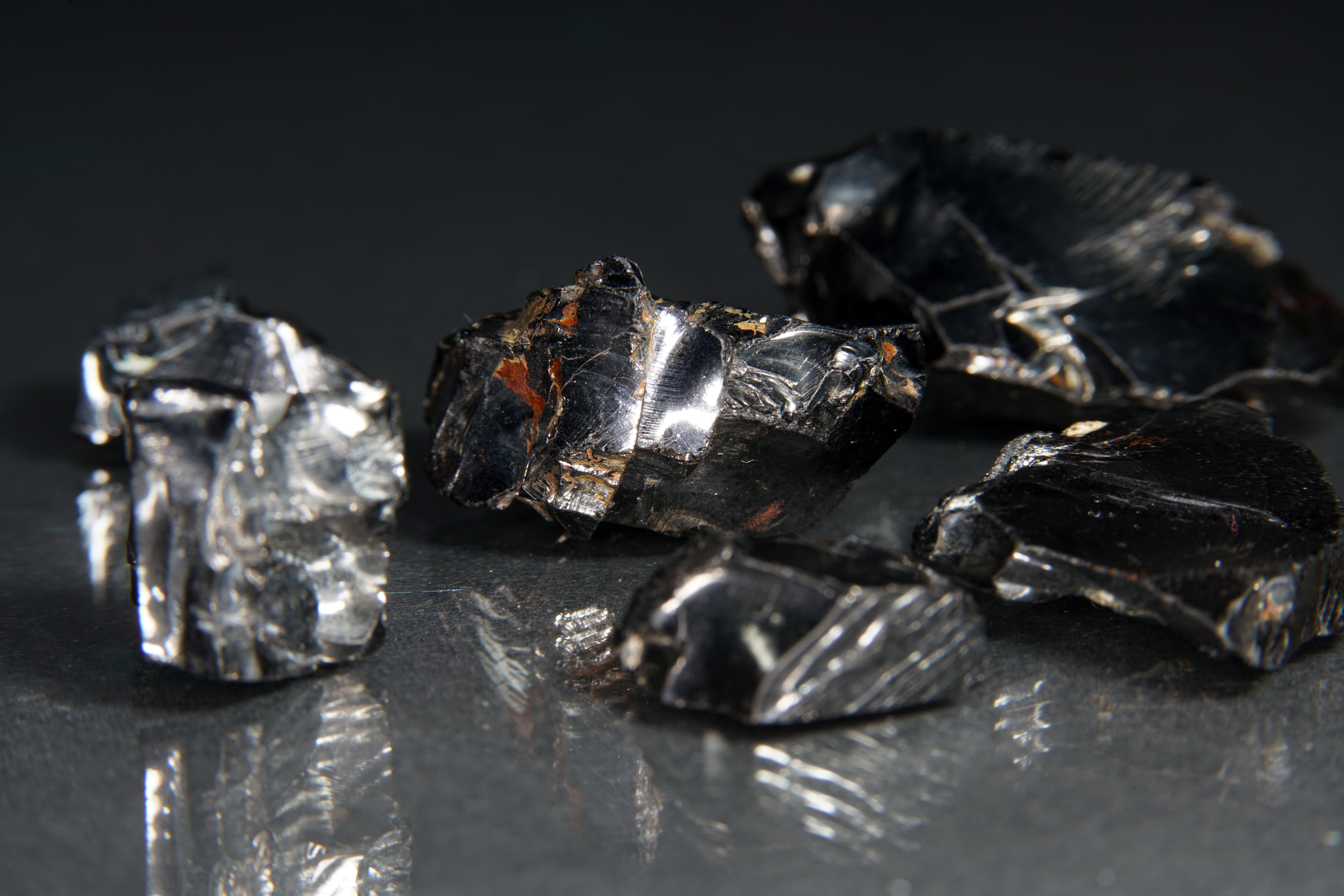

Producing steel can also be CO2 intensive. CRU data shows that making plate steel – typically used for monopile construction – using a blast furnace emits a global median of ~2.4 tCO2/t. Polysilicon and silicon metal production are also potentially highly emission intensive processes.

Despite the high emissions from these inputs, the lifecycle emissions of renewable power are, even today, still significantly lower than for fossil fuel power. But emission targets will tighten, and commodity markets will need to decarbonise also. This will be a huge challenge and consumers of commodity intensive products will likely face higher prices as a result.

Energy and commodity markets are increasingly dependent on one another

The mutual dependency between commodity and energy markets is increasing and is expected to continue as the global economy transitions to a low carbon economy. The world is shifting from a fossil fuel- to a materials-intensive energy system and the needed rate of change is unlike anything we have seen before. The transition will also require a transformation across economies, which will influence our transport, industry, agriculture and building sectors, as well as our societies, on a similar scale. Decarbonising the world will therefore require vast capital expenditure over the coming decades.

Commodity markets are complex, ever changing and subject to multiple forces and a deep understanding is vital when analysing the impacts of the transition. Historically, commodity markets have adapted and many could, at least theoretically, be significantly scaled up and decarbonised. The real question is how best to do this and having a good understanding of costs will be key to achieving this.

Hitting many of the decarbonisation and renewable installation targets across Asia will be extremely challenging. Despite large scale promises and aspirations, supply chains will be stretched and trading relationships are being tested. Having the necessary business intelligence in this space will therefore be needed to navigate these challenges well.

Note: this article was originally published in the Spring issue of Energy Global.