Surging African supply defies market fundamentals

In the past 18 months, weak lithium market fundamentals have triggered a wave of deferrals and curtailments in countries that have historically dominated production, such as Australia and Chile. However, these curtailments have mostly been offset by rapidly growing supply from emerging jurisdictions. Zimbabwe’s newfound importance in supplying lithium has been widely documented, growing from 2% to 10% of global supply since 2022 when prices touched record highs. What is not as widely known is that despite widespread export bans on unprocessed ore, low-grade African direct shipping ore (DSO) and concentrate is streaming out of several other countries, particularly Nigeria.

Chinese entities have been heavily involved in the expanding African lithium industry. Low-grade African ores and concentrates made up 27% of 2024 Q1’s lithium mineral, carbonate, and hydroxide imports into China on a metal-contained basis. This is significantly higher than an average of 13% over 2023, the result of persistent Chinese investment in the region. Upon arriving in southern China, material is transported to inland upgrading facilities before continuing onwards to chemical plants.

Initially, Chinese involvement centred around procuring and aggregating hand-picked spodumene and lepidolite ores bought from artisanal and small-scale miners (ASM), and offering mills, crushing and separation equipment to upgrade ore. Now, these entities are moving to formalise production.

In October, it was announced that construction had begun in Endo, Nigeria, on a $250 M lithium plant capable of processing 18 kt of ore per day. The plant is reportedly backed by Ganfeng Lithium Industry Ltd., Tianqi Lithium Industrial Ltd. and Ningde Era Industrial Ltd, of no relation to the Chinese battery giants that bear the same names.

Since then, construction has been completed on several concentrators in the Nigerian states of Nasarawa and Kaduna. However, it is understood that only one mill, located in Lafia and owned by Avatar New Energy Materials, is currently operating at a low utilisation rate. This is due to unstable power supply, weakening prices, and high costs of importing key consumables.

Where is African lithium coming from?

Using indications of Chinese spot prices, anecdotal reports and regression analysis of trade data, CRU estimates that ASM accounted for almost two-thirds of African supply in 2023. This volume alone was nearly equivalent to the global lithium market surplus last year, highlighting the significance of these operations to the battery value chain.

Nigeria and Zimbabwe, via South Africa, were the largest sources of ASM, although smaller volumes emanated from Mali, Ethiopia, Rwanda and Mozambique, among others. So, with these huge volumes of low-grade material coming out of Africa, it begs the question – where exactly is it coming from?

Almost all of Africa’s lithium originates from ore deposits known as pegmatites, and more specifically LCT pegmatites. Named for their lithium, caesium and tantalum content, LCT pegmatites may also contain economic concentrations of tin, beryllium and gemstones. Although they are found across the globe, including Australia’s giant Greenbushes mine, there are many pegmatite occurrences in Africa. These ore deposits are prime candidates for exploitation by ASM as they are relatively small, require minimal capital input and are often located in developing countries – thus representing a significant income opportunity for local communities.

Like any other commodity, surging ASM lithium supply has been driven by elevated prices, with African exports increasing five-fold in 2023 as spodumene concentrate prices started the year at over $6,000 /t. It is understood that much of the ore originates from former tin and tantalum mines, which were exploited at a time when lithium minerals such as spodumene and lepidolite were considered uneconomic.

Today, these sites can either provide an indication of potential lithium mineralisation, or in some instances already have pre-concentrations of lithium minerals in tailings. Companies are also investigating the possibility of reprocessing tailings for lithium on an industrial scale, including Tantalex’s Manono Tailings Project in the DRC, which historically produced an estimated 150 kt of tin with by-production of tantalum.

What can tin and tantalum tell us about future lithium supply?

The emergence of Nigeria as an important source of lithium may have come as a shock to some given that Nigeria has no resources according to the US Geological Survey. However, this merely highlights the lack of proper resource definitions in some jurisdictions, making it difficult to determine which countries might emerge as key lithium producers in the future.

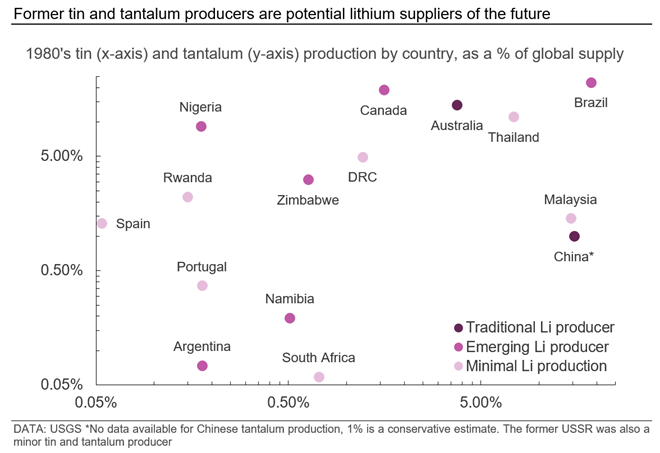

Due to their association with lithium, historical tin and tantalum production may be informative in these circumstances. For example, Australia and China – key historical tin and tantalum suppliers – are also traditional lithium producers. A notable omission is Chile, who along with Argentina, mostly possesses brine rather than pegmatite resources. Of the other emerging lithium producers – Brazil, Canada, Zimbabwe and Nigeria – all were significant producers of tin and tantalum. In Brazil, supply from an increasing number of industrial operations is being bolstered by growing ASM supply in the state of Minas Gerais.

Tin and tantalum from Malaysia and Thailand are mostly derived from alluvial deposits, where dense ore minerals are eroded from a source rock and deposited in economic concentrations. Comparatively, lithium minerals are less dense, more easily eroded and are not found in alluvial deposits. Lepidolite is reported to occur where the bedrock source of these alluvial deposits is exposed. However the rarity of these exposures means that Malaysia and Thailand are unlikely to emerge as key lithium producers.

In the future, the DRC, Rwanda and Namibia could emerge as important suppliers of lithium, while mineral resources are also found in Spain, Portugal and South Africa. Additionally, two key historical tantalum producers – Mozambique and Ethiopia – may also prove substantial future lithium suppliers but are not indicated in the chart below because their pegmatites lack tin mineralisation.

What is next for African supply?

Despite lithium prices hovering around their lowest levels in two years, export volumes of African ore have held relatively firm in 2024, averaging 15 to 20 kt LCE per month. While Nigerian ore has been significantly discounted relative to higher-grade Australian product on a metal-equivalent basis, African concentrate is now generally traded at parity. In reality, Nigerian ore is now at a premium, after accounting for the higher yield losses that result from processing lower grade material.

The Red Sea shipping crisis is partly to blame, altering trade routes and causing freight rates to soar. Drewry Shipping data for May indicates that while east-bound routes have been less affected, west-bound rates from Shanghai have increased 90% y/y and are set to jump even higher in June. These rate hikes are impacting artisanal and industrial operations alike. Zimbabwean industrial operations who were in the project development phase are reportedly no longer able to amortise the cost of west-bound concentrate shipments against east-bound equipment shipments with some incurring significant losses. These cost pressures have led some Chinese processors to source ore domestically rather than import cargoes from Africa, even though lepidolite operations in Jiangxi are among some of the highest cost according to CRU’s Lithium Cost Model. Market players in China now anticipate that appetite for very low-grade African material (<4% Li2O) will reduce over the remainder of the year.

These developments are expected to further accelerate the formalisation of African supply. Western investors have been largely absent in the region, even exiting investments in major projects like Mali’s Goulamina, increasing the Chinese stake in lithium supply. ASM supply has already dropped to about a third of African supply, compared to two-thirds last year, with concentrates (> 3% Li2O) expected to be increasingly favoured over lower-grade DSO (1-2% Li2O) in the future. As is the case with Congolese cobalt, ASM supply of lithium will continue to be price sensitive. Any future price spikes that result from demand shocks are expected to be short-lived, as ASM ramps-up and concentrators come online to take advantage of a booming market.