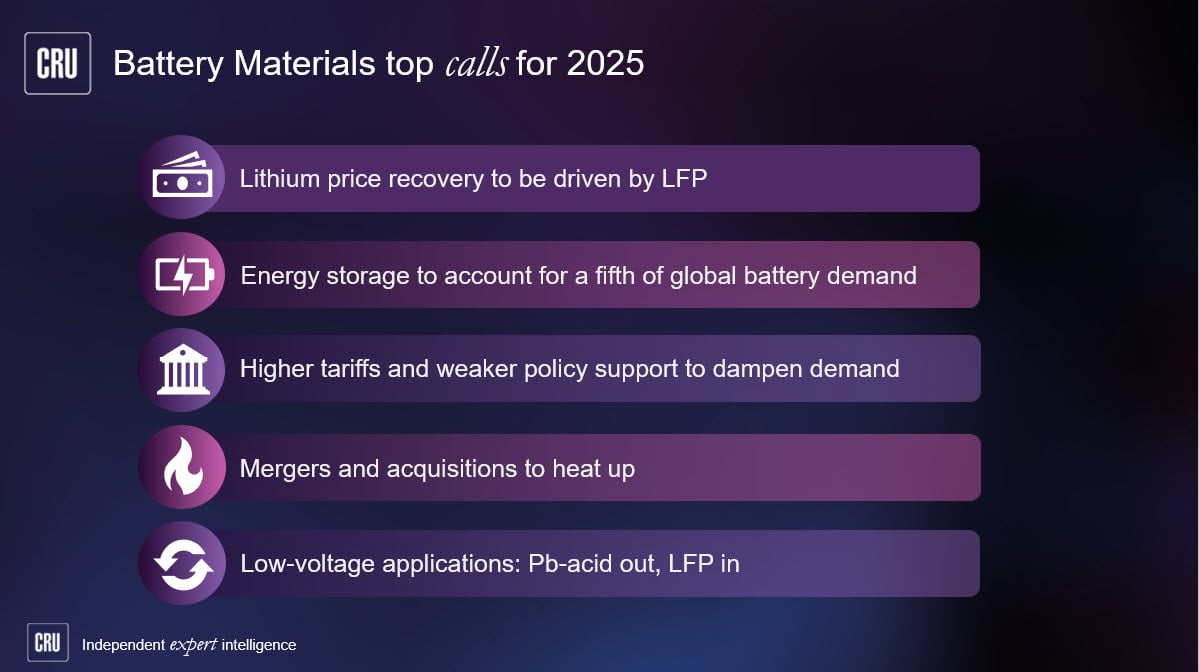

A global supply glut is forcing battery metal miners to rethink their production plans. Despite several curtailments, the outlook for marginal producers remains challenging. However, potential supply shocks and an increasingly segmented battery market will provide some upside potential.

Curtailments hit Aussie miners disproportionately

Between late 2023 and early 2024, slumping battery material prices have forced a spate of closures and production guidance downgrades by nickel, cobalt, and lithium miners, signalling the transition from boom to bust for battery raw material miners. Although operations are being impacted in New Caledonia, Chile and elsewhere, Australian operations have no doubt been hit hardest.

Australian miner IGO has been impacted across its business. It has placed the partially constructed Cosmos Ni-Co project on care and maintenance, hedged production from the soon-to-close Forrestania Ni-Co mine, and downgraded production guidance for the world’s largest Li mine, Greenbushes. While Greenbushes remains highly profitable due to its low cost and high sales price, IGO is prioritising the production of higher-value technical-grade lithium concentrate during the low-price environment.

Core Lithium’s Finniss Lithium Operation has also halted mining but will continue to produce concentrate through the processing of stockpiles. Elsewhere, an expansion at Mineral Resource’s Wodgina mine in Western Australia was delayed from mid-2023 to early 2024, but its commissioning has now been deferred as long as low prices prevail. Overall, CRU expects a decrease in Australian lithium production of 14% q/q in 2024 Q1.

The world’s largest mining company, BHP, has been forced to write down its Western Australian nickel assets by $2.5 bn, amid speculation that it could place its Nickel West operations on care and maintenance and halt construction of its West Musgrave project. Panoramic Resources’ Savannah and Wyloo’s Kambalda Ni-Co operations have been mothballed, while mining has also been halted at First Quantum’s Ravensthorpe. The severity of the situation for many Australian nickel miners has prompted a response from both the Australian Resources Minister and the Premier of Western Australia. However, it remains to be seen whether such a response will be too little too late.

Outside of Australia, ferronickel producers have been among those most strongly impacted, with sizable cutbacks coming from Americano Nickel’s Falcondo and Euronickel Industries in the Dominican Republic and North Macedonia, respectively. The most high-profile casualty has been Glencore’s Koniambo mine in New Caledonia, responsible for an estimated cutback of 28 kt/y Ni. Meanwhile, SQM reduced its 2023 sales guidance for lithium from Salar de Atacama in Chile by 14%. CRU expects that production at the project has been unaffected and SQM is stockpiling the unsold material.

Information drawn from lithium, cobalt and nickel services

Additional supply and dampened demand drive low prices

This recent slew of closures comes as prices of battery chemicals are at some of the lowest levels seen in the last five years, amid persistently oversupplied markets. Although tight Indonesian MHP supply has caused nickel sulphate to rally, prices are still down 28% on March 2022 levels. However, prices of lithium carbonate and cobalt sulphate have fallen much further – 78% and 73%, respectively – over the same period. Prevailing supply gluts have been driven by a combination of weaker-than-expected demand and plentiful supply, predominantly from emerging jurisdictions encouraged by earlier booming prices.

For cobalt, CMOC’s Kisanfu rapidly transitioned from project to the world’s largest mine, while output from Indonesian HPAL operations also doubled y/y in 2023. Much of the additional nickel supply has come from these low-cost Indonesian HPAL operations, whose intermediate product, MHP, overtook the historically-more-abundant nickel matte in late 2023. In the case of lithium, mine supply grew nearly 85% between 2021 and 2023, with Zimbabwean and Chinese lepidolite miners contributing significant volumes along with more traditional producers.

On the demand side, ever evolving battery technologies are reducing consumption. Today, the dominant cathode technologies globally are those with the greatest raw material requirements – medium-nickel NMC cathodes. However, the market share of lithium-iron-phosphate-based (LFP) cathodes has seen a meteoric rise, while western manufacturers are increasingly turning to high-nickel NMC cathodes. In 2023, LFP batteries comprised 58% of BEV production in China, the world’s largest market, where over half of all BEVs were produced last year. Overall, these trends reduce the amount of lithium, nickel and cobalt required to produce a battery of the same capacity.

Additionally, the scaling back of subsidies and targets in major EV markets is an ongoing issue that further weighs on raw material demand. Most recently, late 2023 saw the scrapping of subsidies in Europe’s largest EV market – Germany – causing European EV sales to drop. These factors, when coupled with improving electrochemical performance of cathodes and improving yield rates, are dampening demand.

Data drawn from Battery Value Chain Service

What is next for marginal producers?

Further mine closures will be forthcoming over the next couple of years, although they are not expected to be sufficient to turn surplus into meaningful deficit and transform the fortunes of battery raw material miners. However, Australian nickel-cobalt miners may be able to capitalise on an increasingly segmented battery metals market. Under the US Inflation Reduction Act, electric vehicle batteries containing a certain value proportion of raw materials extracted or processed in a free trade agreement country are eligible for up to $3,750 in tax credits per vehicle.

Furthermore, from 2025, the Foreign Entity of Concern (FEOC) rule will come into effect for raw materials, excluding vehicles containing any material extracted or processed in countries designated as ‘Foreign Entities of Concern’ – namely China, Russia, Iran and North Korea – from accessing subsidies. Similarly, material mined or processed by companies that are linked to the governments of these countries will also fall under the FEOC designation. This rule may result in an IRA premium for Australian miners, considering the paucity of IRA compliant supply in some commodity markets (e.g. <10% of mine supply for nickel and cobalt), and that most extraction or processing is conducted by Chinese companies or in China.

Another potential premium centres around ESG-compliant material, with several Australian miners pressuring the LME to introduce separate prices for ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ nickel. Accessing a ‘green’ premium would allow Australian miners to better compete with the world’s largest producer, Indonesia, which suffers from environmental issues including tailings disposal and carbon-intensive extraction techniques. However, the extent to which Australian production can be classified as comparatively ‘green’ is debateable, given that both countries utilise similar processing techniques, and that both countries rely heavily on non-renewable energy sources.

For lithium, CRU’s Lithium Cost Service identifies Chinese lepidolite and smaller non-Chinese miners as those at greatest risk of curtailment. Many of these producers will be ineligible for potential IRA or green premia, and may be forced to close. However, the small number of operations and a high exposure to battery demand means that the lithium market is more susceptible to supply shocks. Chinese lepidolite producers will be able to rapidly restart production during supply shocks, helping to bridge the supply gap in much the same way as Congolese artisanal cobalt miners do.