India has all the makings of becoming the driving force of the global steel industry. As China cuts steel capacity, India could be stirring for rapid acceleration in growth, but obstacles remain.

China’s consolidation of its steel sector through planned capacity cuts, as well as stricter environment norms and mining safety inspections, has had a massive impact on the global steel industry. But, while China grapples with overcapacity issues, it is time to turn the spotlight on India, which is projected to be the single largest driver of steel demand in the next 20 years, with capacity estimated to rise over 50%. Indeed, with similar population numbers, India’s steel intensity of 61 kg per capita against China’s 647 kg per capita calls for attention to the massive expansion potential that the country holds.

Although there is a rationale for India to scale-up its steel making capacity, we discuss the impediments faced by the country that will make this journey challenging. Bureaucratic roadblocks to project implementation, credibility of government mandates and incentives and supply chain management of key raw materials are some of the major challenges discussed. Alongside this, we also look at the signs of progress observed in recent times.

The elephant in the room

India’s steel growth targets are often criticised for being overambitious and that is the very reason that the initial buzz created by any new scheme or expansion plan quickly fizzles out. On top of this, the opaque and complex nature of the steel sector’s workings across different states, as well as political influence, especially in the mining industry, makes it harder to digest the optimism around growth plans. However, it is noteworthy that, despite the hurdles India faces, it has managed an average steel production growth of 5.6% in the last five years and now has the third largest steel industry after China and Japan, having displaced the USA in 2015. This growth is underpinned by the leading economic growth of 7.9% witnessed in 2016 against global growth of 2.4%. India may not be ready to soar, but it can surely run.

In addition, the prompt measures taken by the Steel Ministry in recent times show their renewed willingness to support a domestic steel industry and, perhaps, signal their intent. Notably:

- the imposition of minimum steel import prices in 2015, contrary to global trade rules

- followed up by antidumping duties on select steel products

- antidumping duties on metallurgical coke from Australia and China

- dedication of over 25% of rail capacity to the steel sector

- preferential auctioning of coal and iron ore mines to forward-integrated steel players.

The Ministry is also promptly addressing grievances received from the industry that has led to some key measures, such as:

- coal allocation to the sponge iron industry

- scrapping of the ‘one coal mine-one washery’ system

- reducing the minimum number of bidders for mine auctions

- infrastructure improvements through the on-going Sagarmala project for port development and

- investments in rail capacity expansion

Sky-high capacity targets driven by demand expectations

Based on extensive research of end-use demand, we forecast that finished steel consumption in India will reach 197 Mt by 2030, against the 230 Mt projected by the National Steel Policy for 2031. This is a massive jump from the steel consumption of 81.6 Mt in fiscal year 2016, as quoted by the National Steel Policy, and will be largely driven by investment in infrastructure. However, the big question is – how will India meet this demand?

We expect capacity additions through brownfield projects, greenfield projects, inorganic growth (i.e. the acquisition of distressed assets) and organic growth. At present, growth in the Indian steel sector is focused around the organic and inorganic routes possibly because other options are relatively more expensive and challenging to follow through. The latter has been prompted by the new statutory guidelines that are bringing many stressed assets in the industry under the hammer, leading to consolidation through potential acquisition by existing steelmakers. Organic growth is taking place through debottlenecking investments that should add roughly 10 Mt capacity of additional capacity. As for brownfield projects, over 10 Mt/y of potential capacity expansions have been identified, chief among these are the JSW Dolvi expansion from 5 Mt/y to 10 Mt/y and the Tata Kalinganagar expansion from 3 Mt/y to 8 Mt/y. JSPL has already added 3.5 Mt/y at its Angul facility in 2017. A prominent greenfield project coming up in 2021 is NMDC’s Nagnar project, with 3 Mt/y capacity.

Plentiful iron ore

India has vast reserves of haematite ore that are chiefly mined in the states of Odisha, Chattisgarh, Jharkhand, Karnataka and Goa. The industry is recovering from mining bans imposed in 2012 for illegal mining that made India a net importer of ore from 2012 to 2015 and led to the enforcement of mining limits across the sector in accordance with environment norms. To secure the domestic supply of ore for the industry, many expansion plans are in the pipeline, led by state mining giant, NMDC, that plans to expand from its current capacity of 48 Mt/y to 67 Mt/y by 2030. In addition, the Indian government is encouraging backward integration through the auction of expired mining leases to steel mills. By 2020, over 60 Mt of iron ore in Odisha is cited to be under auction due to the expiry of several merchant mining leases. Recently, JSW Steel, with 18 Mt/y crude steel capacity, was allocated five iron ore mines that will render its procurement costs cheaper by $10 /t, as discussed in our Special Feature on pricing dynamics in Karnataka. Integrated producers currently hold a preference for brownfield mines to secure captive iron ore, rather than undergoing the tedious and long process of valuation of a new mine and seeking environment permits; starting production from a new mine takes an average six years. In addition to increasing captive ownership of iron ore mines, the government is also looking to provide a pricing formula to ensure more uniform and stable pricing for domestic iron ore.

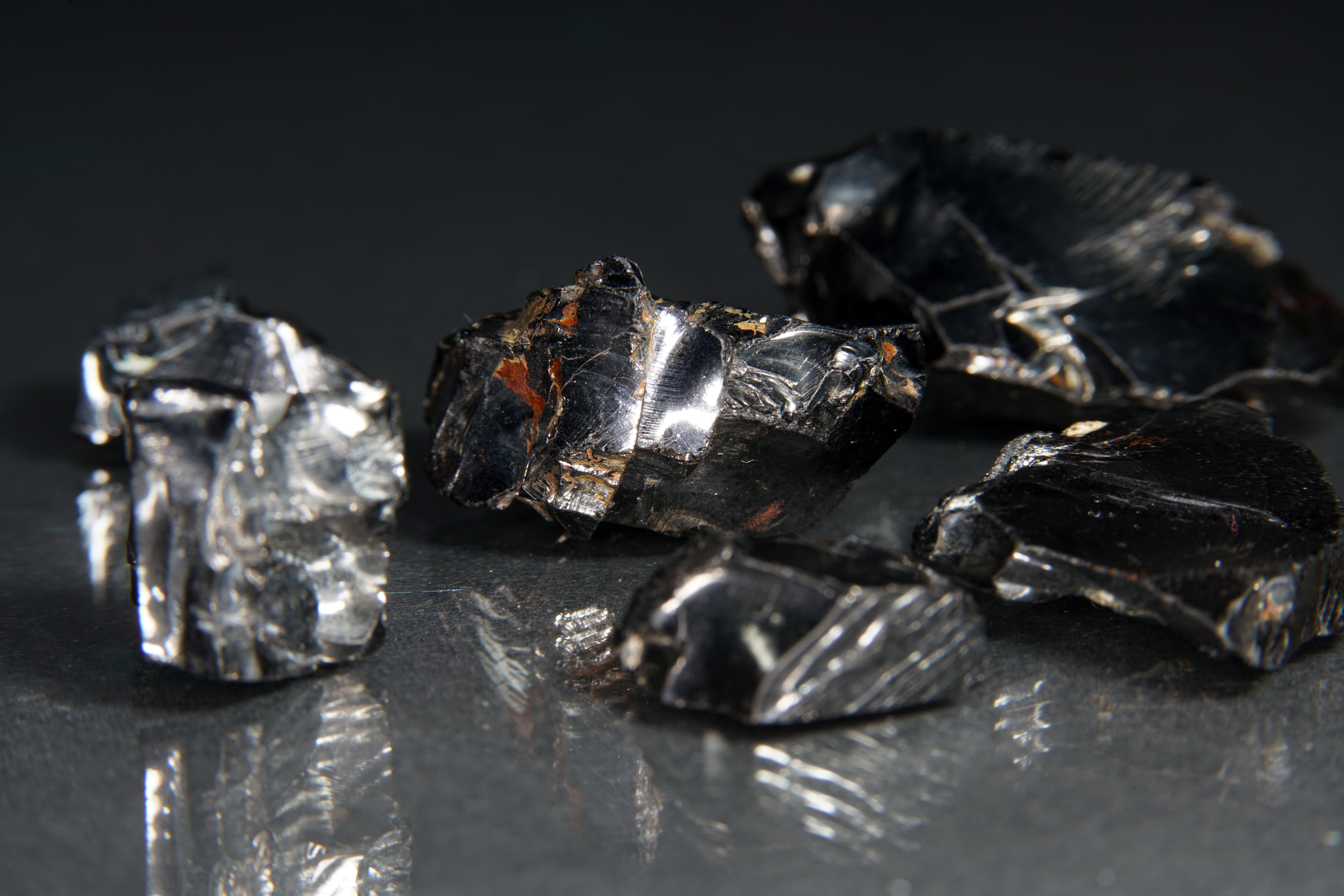

Metallurgical coal remains an obstacle to overcome

Although India inherits vast reserves of iron ore, it lacks availability of the other key ingredient of steelmaking – coking coal. Current coking coal imports, from Australia and South Africa amongst others, amount to 70% of the total requirement. The domestic supply of coking coal is of poor quality due to a high ash content, which varies from 19% to 21% and leads to high costs at the hot metal stage.

The country also imports small amounts of metallurgical coke, as merchant coke has proven to be high cost due to the prevalence of inefficient technologies. Overall, more than half of the 40 Mt/y domestic coke capacity consists of captive coke operations, which have provisions for by-product recovery or waste heat recovery, making them, on average, $32 /t more cost efficient than merchant coke producers. Such merchant producers face strong competition from Chinese coke imports into India. Our research shows that these merchant coke producers are hesitant about making investments for technology upgradation because of concerns about securing sufficient coking coal supply and, thus, they will continue to face competition from Chinese coke in particular. We expect met. coke imports to grow by 25% from 2016 to 2021.

Growing domestic scrap

India’s current consumption of scrap is ~31 Mt, of which 17% was imported in 2016. Considering that the National Steel Policy encourages steel capacity growth through the EAF and IF(i.e. induction furnace) route, which are scrap-based production units, the government has proposed better scrap availability through the installation of auto-shredding units in the country. On 01 April, the Indian Supreme Court banned the registration and sale of vehicles non-compliant with the latest emission norms (i.e. Euro IV). This bold move by the court is in accordance with the government’s vehicle scrapping policy which, when implemented, will phase out of vehicles bought on or before March 2005. It will also ensure better regulation for recycled scrap, as discussed in detail in our insight on auto-recyling growth in India. Although no timeline has yet been set, auto-shredding plants planned to be set up will feed on this vast fleet of scrapped vehicles. As the Indian scrap fund increases, we expect scrap imports to reduce by a noteworthy 70% by 2030.

Slow but steady progress in thermal coal

To achieve the aforesaid steel expansion plans, a cheaply available power supply will be essential. Currently, Indian power tariffs are among the highest in the world due to the high cost of generation and transmission arising primarily from power theft, technical losses, cross-subsidies and high coal procurement costs. To address these issues, the government has come up with several schemes targeting the problem areas. For instance, the UDAY scheme aims to improve the financial health of the state-owned distribution companies by providing a prolonged debt repayment schedule for states, while these states better their revenue realisation through improvements in billing and collection efficiency . Meanwhile, to provide a secure flow of domestic coal, the government is aiming to boost Coal India’s production and has already given a directive to state-owned power utilities to only consume domestic coal, indicating their confidence in the domestic coal supply.

From importing close to 170 Mt in 2014 to 148 Mt in 2016, India has made strides in improving its domestic coal production. Having said that, there is still a long way to go for further improvement in domestic availability of coal – like improving coal quality through the installation of more washeries and narrowing the gap between delivered grade and declared grade of coal, increasing railway capacity for efficient coal delivery, faster response on environment permits, reducing costs by improving labour productivity alongside bringing more mines under the Mine Development-cum-Operator (MDO) model. The chart below shows how high power costs affect power intensive steel raw material industries, such as ferroalloys.

CRU view of current developments

The government has set a target of 300 Mt steel capacity for 2030, which we have analysed as unnecessary, but is also highly unlikely (see below). Based on a detailed analysis of domestic end-use demand, we believe that Indian finished steel demand will reach close to 200 Mt, for which CRU’s forecast of crude steel capacity of 250 Mt would be sufficient.

Interestingly, whilst China has fully closed down its IF sector, the National Steel Policy is encouraging IF capacity expansions, alongside EAF and BOF expansions. Our view is that the encouragement of IF capacity is, essentially, an admission by the Government that its capacity expansion plans will be difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. Steelmakers still face significant problems to gain planning permission for greenfield expansions and it is no easier today to progress the construction of a large integrated steel mill than it has proven in the past. POSCO recognise this and have finally given up on their 12 Mt steel project in Odisha after 12 years of trying to negotiate regulatory hurdles.

The voluntary scrapping of vehicles bought before 2005 could, potentially, bring forth a lot of high-quality scrap. The government is finalising this policy, but they will essentially provide attractive discounts for new automobiles to encourage car users to divert their old vehicles for scrap instead of selling them into the secondary/tertiary market. However, the journey to more domestic scrap may be a rough one. A cost-benefit analysis of the incentives may show positive returns in the long run for the economy, but their impact on the car market in the short-term and ability of the steel industry to take advantage, given mounting debts in the sector, is unknown. Furthermore, auto-shredding units are power intensive and, given the increasing number of power projects jammed in the pipeline, installing dedicated power plants for these projects may be a prolonged process.

Ultimately, India will have to build its steel industry based on the BF/BOF route; this is the only route that can provide the scale required to support the anticipated growth. The iron ore required to support this expansion is available and we believe India will be largely self-sufficent. However, metallurgical coal will remain in deficit and imports will be required. Indian has few reserves of accessible metallurgical coal and the quality is poor. Washing and upgradation is possible, but this will be costly and India will not be able to achieve self-sufficiency.

Attempts by the government to improve the situation on the ground are also not always as helpful as planned. The recent requirements for state-owned utilities to only burn domestic coal are laudable, but they fail to take into account the reality of coal availability in the country. India requires large volumes of imports to generate the power it needs and simply stipulating that public utilities must burn domestic coal does not change this reality. In fact, all this policy has done to date is to turn the domestic logistics system on its head, as coal supply is diverted to public utilities. This has required locomotives and rakes to be redeployed, which has under-mined, at least partially, the integrity of the logistics set up. As a result, imported coal sits on the port, inventory is building at mines, whilst many power stations are running with critically low supplies.

Conclusion

We envisage that India will require ~250 Mt of crude steel capacity by 2030 to support an expected finished steel demand of close to 200 Mt and such expansion should be possible. However, this requires that project promoters will be able to obtain the relevant permissions to build the steel plants, which has proven difficult, if not impossible in some cases, in the past.

We believe that, whilst government attempts to improve conditions to encourage the development of steel capacity are useful, there is a danger that this development could become unbalanced. That is, currently, there are moves to enable iron ore reserves to be better exploited but, if steel production cannot pick up as rapidly, this could lead to over-supply.

The government’s requirements for public utilities to burn only domestic coal are a case in point. Whilst this directive was to encourage greater domestic supply, with that supply not currently available, the policy has simply led to short-falls, power shortages and increased tariffs. The encouragement of IF capacity or the expectation that investment in scrap processing will raise the level of scrap available are other examples of un-connected thinking.

To redeem India’s image in terms of ‘ease of doing business’, the government must make permit issuance a timebound process and make auctions a more transparent and simple procedure so investors have sufficient information to engage in realistic project planning. While current developments in the sector, as listed in this paper, inspire confidence in India’s growth story, it is not a ‘done deal’ and continued vigilance is necessary.

CRU has an office in Mumbai and its analysts are well-connected with a wide network of industry players. We understand the constraints across the steel value chain and are able to analyse policy announcements and their potential impact on pricing and profitability of the sector. If you want to talk to us about any aspects of the Indian market, please get in touch using the details provided in this insight.