The 2024 US elections: what it means for policy

The US presidential elections will take place on 5 November 2024. After lagging behind Biden throughout most of this year, polls in key swing states are now very close, and a Trump victory is now seen as an equally likely possibility by betting markets. In this Insight, we evaluate potential impacts of the US elections on key parts of the economy. Overall, although some policies might be rolled back or adjusted if a Republican was to replace Biden, 180° turns are unlikely in most areas. A White House which promotes either free trade or fiscal conservatism is very unlikely to emerge from these elections.

The single most important policy change under a Trump presidency might be the lack of predictability. Under Biden, the direction of US policy is relatively clear – use the US’s economic and political sway to try and contain Chinese power, while using subsidies, trade restrictions and regulation at home to decarbonise the economy and boost the industrial base. Having not participated in the debates and having given little indication of concrete policy proposals, it is highly unclear what direction a Trump White House would take on many issues.

Green transition: Progress might stagnate

One of Trump’s first acts as president in 2017 was to pull the US out of the Paris Agreement on climate change (which Biden re-joined upon taking office). It is highly likely that Trump – or another Republican – would do the same were they to win in 2024. At minimum, this would be a huge symbolic blow to the decarbonisation agenda worldwide and would weaken prospects for demand growth in the many commodities linked to the energy transition.

However, this would not automatically mean reversal of actual Federal policy. The president alone cannot reverse existing legislation such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). New legislation to cancel or repurpose IRA funding would have to pass Congress. Moreover, according to the White House, about $337 billion of investment under the IRA will go on solar, wind and storage projects located in the “red” states, and so Republicans in congress will have strong reasons to maintain much of the IRA incentives. A plausible outcome, however, might be that the IRA gets re-written and made somewhat less generous, and even more protectionist.

State-level policies pushing decarbonisation – in particular, in California and other – would also probably continue under a Republican administration. These have been an important part of the policy picture in the US.

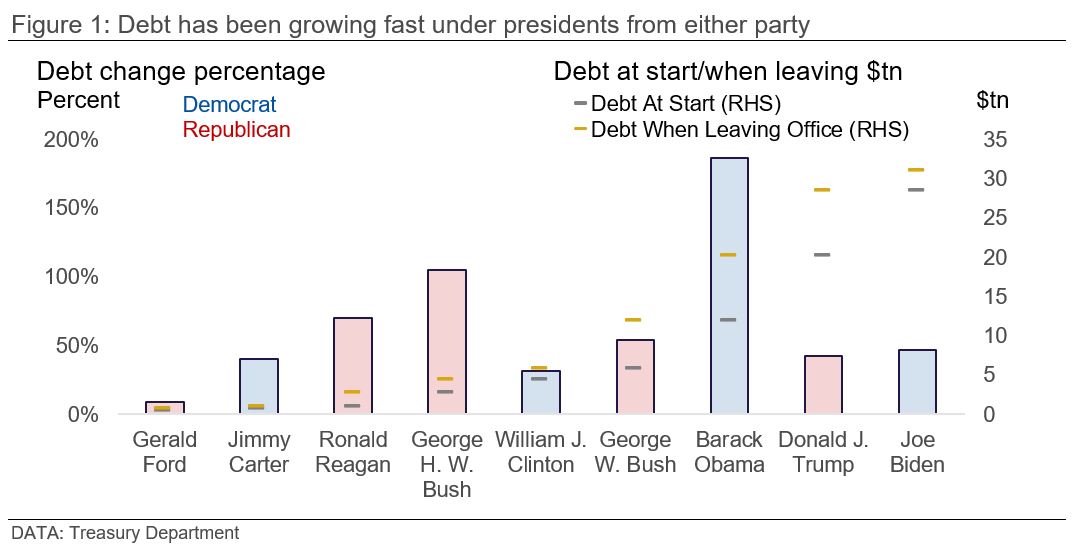

Debt: Trillion dollar deficits will continue

We expect the US to run a fiscal deficit of almost 7.5% in 2023 – a huge number considering the economy is close to or at full employment. US debt has been growing rapidly over the last few decades under both Republican and Democratic presidents (Figure 1), so we have little expectation that the US will copy Europe in attempting to bring down deficits. Perhaps the most likely scenario for fiscal consolidation would be if a more ‘traditional’ Republican wins, although given the extent of the increase in debt seen under GW Bush shows even this cannot be counted on.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimated that cumulative deficits from next year to 2033 will come as high as $20.3, crowding out investment and weighing on growth; while interest costs are projected to expand from $476 billion in 2022 to $1.4 trillion by 2033. In 2023, spending on net interest costs outpaced spending on Medicaid and Income Security Programs. According to Peter G. Peterson Foundation, in 2022 72% of democrats, 74% of independents and 86% of republicans felt the mounting debt should be a top-three priority. Hence, it cannot be completely ignored by a president from either party.

In our recent insight we discuss in greater detail potential impact of US elections on other parts of the economy.

Explore this topic with CRU